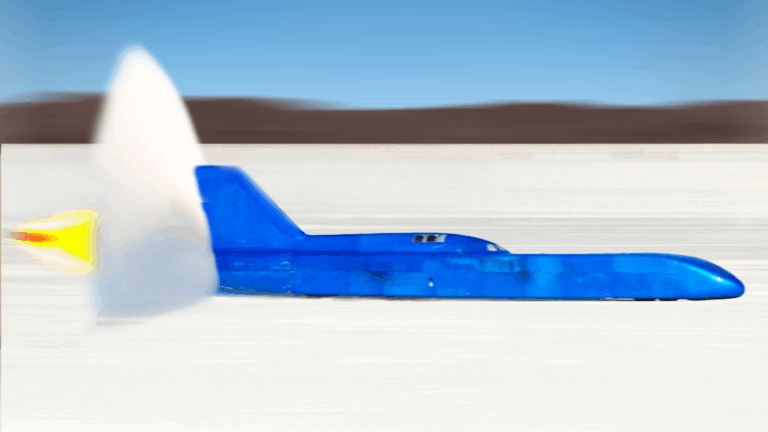

At 763 mph, the Thrust SSC became the first car to break the sound barrier in 1997. But pushing past 1000 mph presents engineering challenges that make this feat potentially impossible on land – and it’s not for the reasons you might expect.

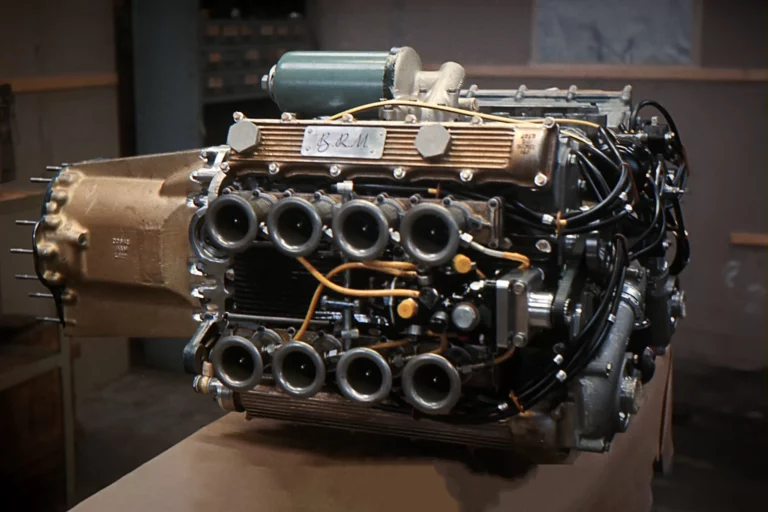

Dr Ben Evans, who worked on the Thrust SSC project, explains that the real problem isn’t the sound barrier itself. “Does anything fundamentally change when you go from Mach 0.999 to Mach 1.001? Well, not really,” he reveals. The sound barrier isn’t actually a barrier at all.

The first shock waves appear at around 540 mph – long before the car reaches supersonic speeds. These form underneath the rear suspension as air accelerates around the vehicle’s curves, creating pockets of supersonic airflow whilst the rest remains subsonic. This transonic regime creates incredibly unstable conditions with shock waves constantly shifting position.

At supersonic speeds, the shock waves become powerful enough to literally tear up the ground beneath the car. The Thrust SSC’s rear wheels weren’t running on solid ground – they were travelling through a cloud of loose desert surface displaced by the shock waves. At 1000 mph, these effects would be catastrophic.

The biggest challenge isn’t engineering or aerodynamics – it’s finding somewhere to do it. You need over four miles to accelerate to 1000 mph, then the same distance to stop safely. The shock waves damage the surface so severely that the return run must use a different line. With mountains at one end and roads at the other, suitable locations are vanishingly rare.