Formula 1 drivers are some of the world’s most skilled overtakers, trained to find the perfect moment to “send it” and outbrake opponents from speeds of 180 mph down to below 60, all while managing the intense forces that come with 6G braking. But what specific techniques do they use to get past a fiercely defending driver? Let’s dive into the mechanics of F1 overtaking, breaking down each approach these elite drivers use when fighting for position on the track.

The Art of Outbraking: Inside Moves

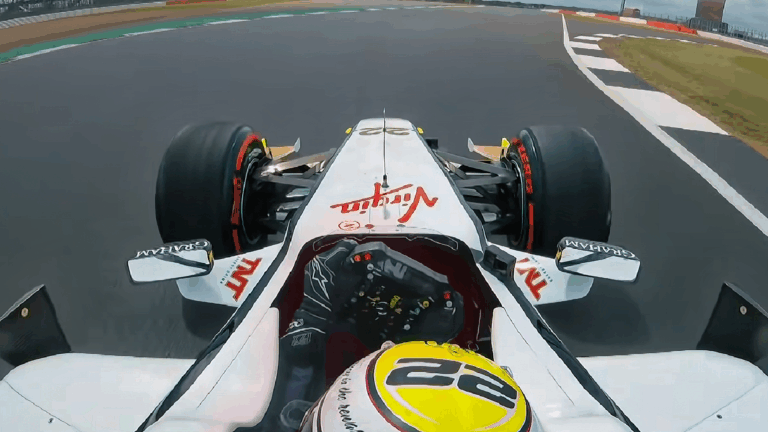

One of the most straightforward overtaking techniques in Formula 1 is the inside braking maneuver. Here, a driver gains a run down a straight, then “sends it” by braking later than the car ahead, moving up the inside. The key is to position the car perfectly straight during braking to optimize stopping efficiency and avoid locking up. This move is all about focus and precision since it sacrifices some cornering speed to ensure position gain.

While it might sound straightforward, pulling off a clean inside move demands incredible anticipation and timing. The defending driver typically brakes to optimize their corner speed for the fastest lap time, whereas the overtaker sacrifices that ideal line for position. This willingness to overslow can sometimes cost both drivers time but often pays off with a successful pass, as seen in classic moves from Hamilton’s early GP2 career, where he would find just enough room to gain critical positions.

Catching Them Off Guard: The Late Braking Maneuver

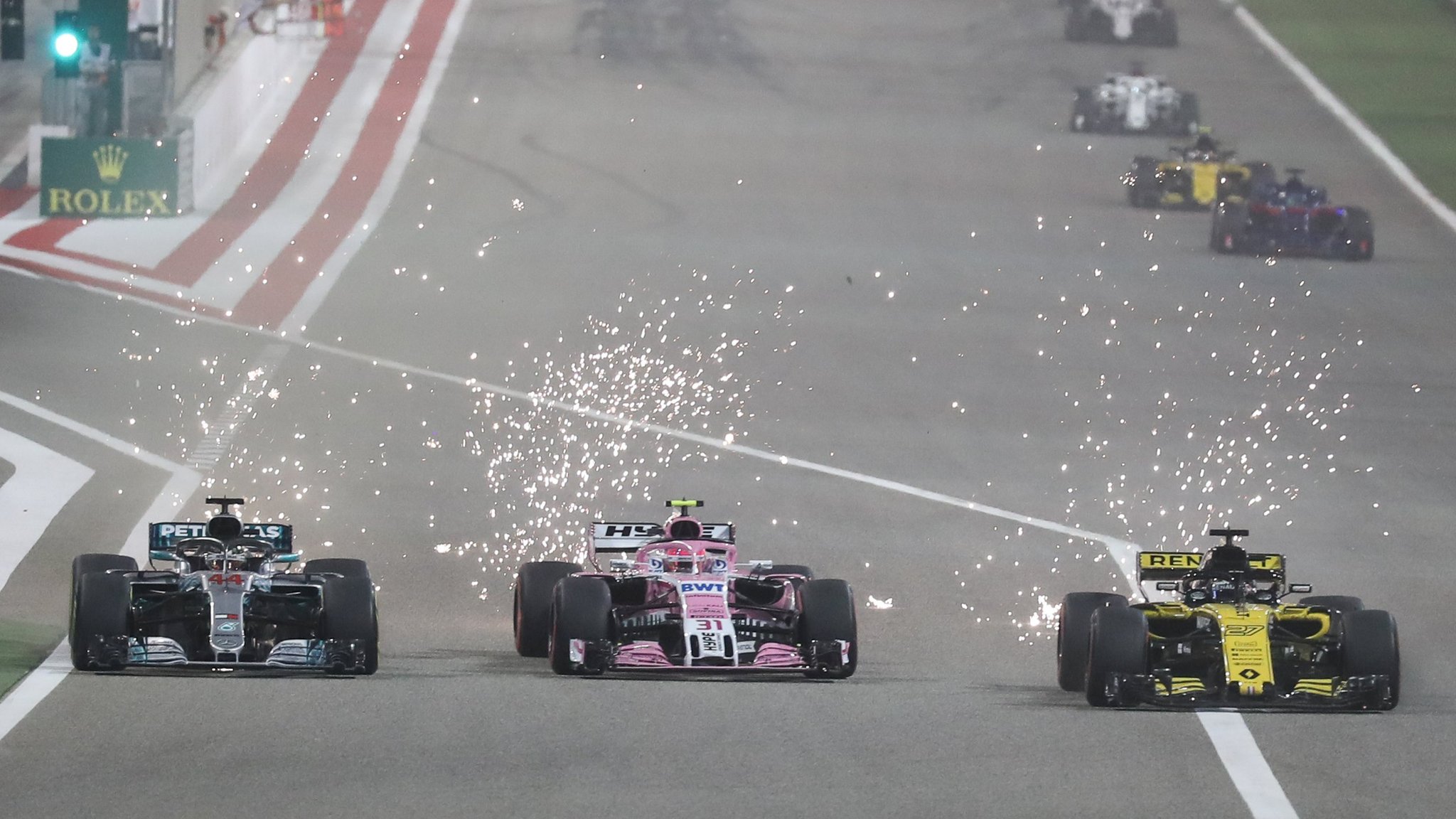

A more daring tactic is the late braking move, often executed from further back with minimal warning to catch the other driver by surprise. In this approach, the attacking driver dives down the inside at the last possible moment, forcing a race to the apex with the defender. This “late send” maneuver is high-risk and demands absolute control under braking, as seen famously in Daniel Ricciardo’s iconic dives during his career.

Late braking moves showcase a driver’s skill in finding unexpected gaps. However, it’s not often seen in modern F1 due to DRS (Drag Reduction System), which makes overtaking simpler on straights but can remove some of the raw excitement of these split-second judgment calls.

Outside Lines: The High-Speed Challenge

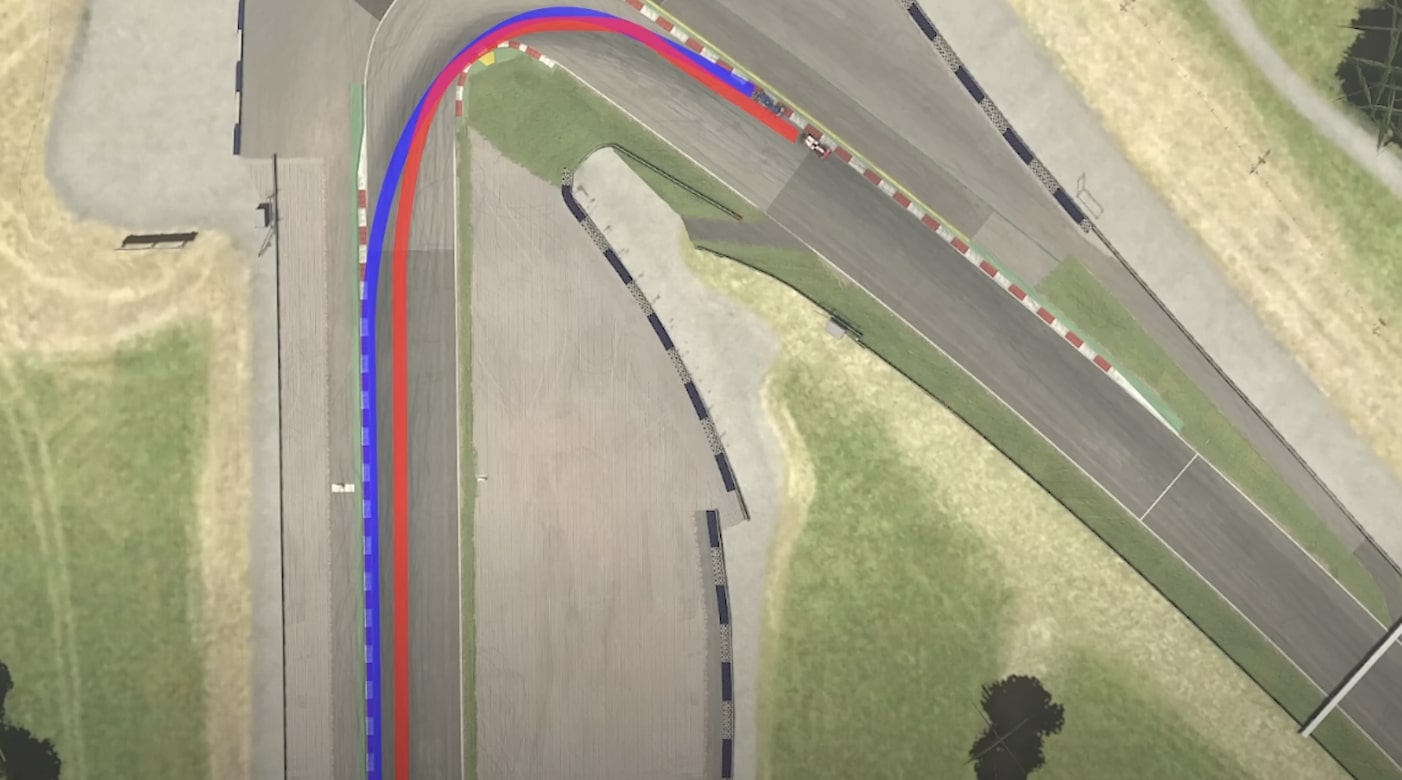

When the inside line is blocked, drivers can opt to go around the outside. This path requires significantly higher cornering speed and control, as it’s a longer route that depends on the attacking driver’s pace advantage. An outside move takes immense commitment, sometimes aided by factors like wet track conditions or fresh tyres for added grip.

A well-executed outside move can surprise both the defending driver and spectators, as demonstrated by remarkable wet-weather overtakes. For instance, the 2013 DTM race showcased a driver adapting his line for extra grip, managing to carry momentum around the outside. Here, the overtaker’s line control on exit forced the defender to concede position, a testament to the effectiveness of outside moves under the right circumstances.

Maximizing the Switchback: Timing the Pivot

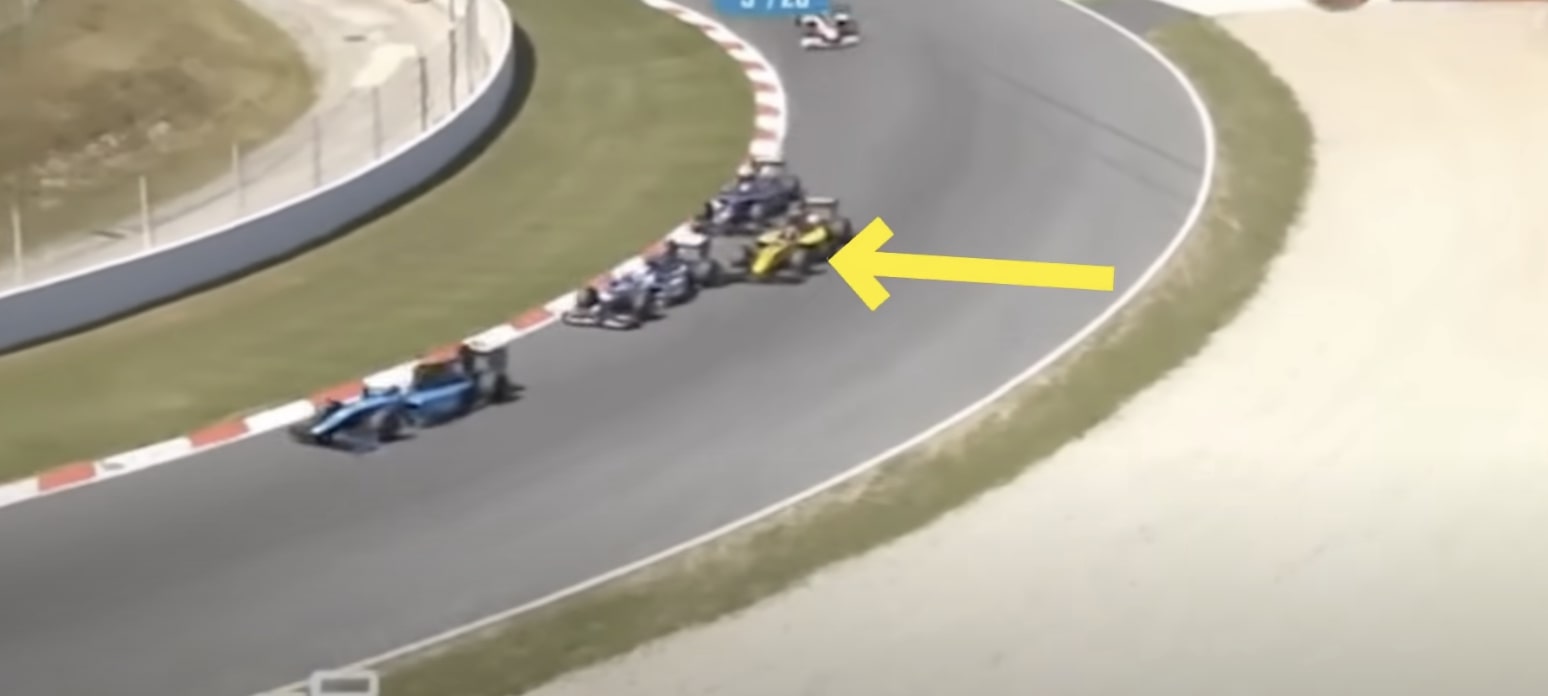

When a defending driver successfully covers the inside line, a classic “switchback” or “switcheroo” maneuver can be the answer. This move involves sending the car down the outside, then pivoting tightly to regain position on the inside through the corner exit. The goal is to capitalize on the defender’s compromised entry speed, using a tighter exit to gain acceleration down the next straight.

The switchback can work defensively as well as offensively, adding a layer of versatility. However, a skilled defending driver can counter the switchback by lingering at the apex, effectively blocking the overtaker’s line. This tactic requires finesse, as it can lead to contact if not executed with caution, making it a high-stakes yet powerful move.

Building Pressure: Creating Opportunities

Sometimes, overtaking is a game of patience. When other moves fail, F1 drivers can apply pressure, staying close and repeatedly attempting different lines to force an error. This relentless pursuit affects the defending driver’s focus, increasing their chances of missing a braking point or understeering. By staying in the mirrors, the attacker can manipulate the defending driver into a compromised line, eventually leading to a mistake.

A classic example of this was seen in the British Touring Car Championship, where drivers displayed persistence by probing every line available. By maintaining this close-quarter pressure, an attacker can exploit even the smallest gap, allowing a cleaner pass with less risk.