Ayrton Senna won more than half of the wet races he entered – a statistic that puts him significantly ahead of other legendary wet weather drivers like Michael Schumacher, Lewis Hamilton, and Max Verstappen. But this wasn’t natural talent; it was the result of systematic learning from early failure.

Senna’s first wet race in go-karts was, in his own words, “a disaster – just a complete joke.” Rather than accept this weakness, he transformed it into his greatest strength through methodical practice and deep technical understanding. Every time it rained, he’d be out there pushing himself to understand every aspect of wet driving.

The 1984 Monaco Grand Prix announced his arrival to Formula 1. Starting 13th in an uncompetitive Toleman, Senna carved through the field as conditions worsened, reaching second place by lap 19 and closing on leader Alain Prost before officials stopped the race. Though he didn’t win, Formula 1 had witnessed his arrival.

His first F1 victory came in equally dramatic fashion at the 1985 Portuguese Grand Prix. In torrential conditions, Senna was half a second faster than Prost in qualifying, then dominated the race completely. By lap 20, he was already 30 seconds ahead, eventually winning by over a minute and lapping everyone except second place.

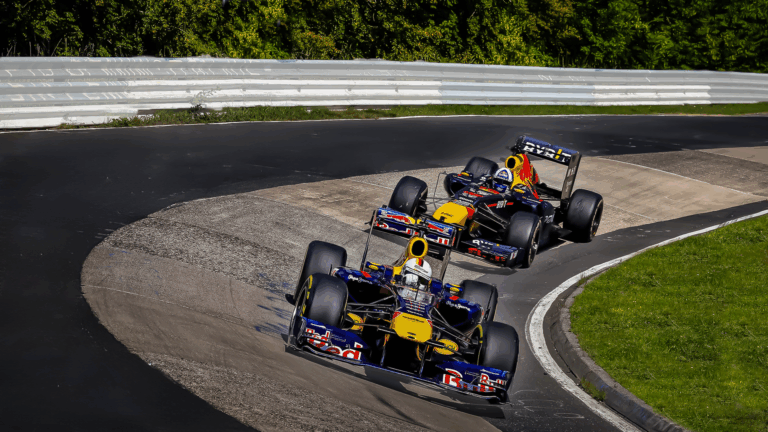

But perhaps his most famous wet performance was Donington 1993 – the “lap of the gods.” Starting fifth, Senna overtook Schumacher, Wendlinger, Hill, and Prost on the first lap alone, then destroyed the field to finish 1 minute 23 seconds ahead. He even set the fastest lap by using the pit lane shortcut – a strategic masterstroke showing his incredible attention to detail.

What made Senna special wasn’t just car control – it was his systematic approach to wet weather setup. He obsessed over getting the engine running as smoothly as possible in wet conditions, understanding suspension geometry, and providing incredibly detailed feedback to engineers. In an era before millions of data points, driver input was crucial.

His technical understanding combined with extraordinary mental capacity. Engineers were astounded that his post-session feedback matched exactly what their data loggers showed. He could detach his mind from the physical demands of driving, allowing him to process and recall every detail of a lap whilst operating at the absolute limit.

Crucially, Senna understood that being fast in the wet wasn’t about bravery – it was about control. “Better if you feel in control of what you’re doing,” he explained. “You dictate the moves and make things happen instead of waiting for other people to make errors.” This confidence allowed him to find grip where others couldn’t, staying off the racing line to avoid rubber buildup.